The Good Wife, Episode Three: “A Precious Commodity”

I always knew it would happen; I just didn’t realize it would be so soon. The “perfect couple” seems headed for divorce.

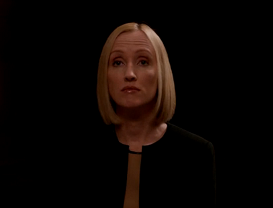

“A Precious Commodity” picks up where the previous episode left off: Diane, believing it to be a prerequisite for gaining the Chief Justice’s support for her nomination to the Illinois supreme court, has just given an interview criticizing Will for, among other things, having once stolen money from a client. The first image to appear onscreen is a lengthy, extreme close-up on Diane’s face as she silently processes the damage her decision will cause—to Will, to the firm, to herself. This moment sets up the episode’s narrative focus—while Alicia’s surrogate mom/abortion case subplot gets its share of screen time, the forty-three minutes that follow play as Diane’s tragedy.

I was surprised at how successfully the writers handled the Diane-Will breakup this episode, given what a sloppy job they’ve done setting it up. Until the final minute of last episode (“The Bit Bucket”), Diane appeared adamant in her refusal to bad-mouth Will. The writers never show what changed her mind. Furthermore, her betrayal proves unnecessary: just as she finishes the interview, a call comes through from Eli saying that they’ve found another way to gain the Chief Justice’s support (Peter threatened him somehow). While this twist does make Diane’s position even more painful—her betrayal was all for nothing!—fictional tragedies lose the weight lent by inevitability when they depend on accidents or, in this case, administrative incompetence, to push conflict over the edge into catastrophe.

Christine Baransky’s performance anchored the episode. Diane is profoundly unsentimental—a quality too rare in female TV characters. Throughout the episode, Baransky strikes a perfect balance between Diane’s customary steeliness and her profound sense of hurt and guilt. She faces down the other partners with a fierce physical stillness that underscores her undiminished sense of command. Will excepted, the other partners appear as pygmies by comparison. At the same time, her defiance masks an increasing desperation; Diane’s repeated rejection of various proffered severance packages reflects not greed but a refusal to accept that her relationship with Lockhart Gardner has ended.

Christine Baransky as Diane. Image via Vulture.

The episode’s most telling scene, however, is one built around Diane’s absence rather than presence. Will summons every partner except Diane to a secret meeting on the twenty-seventh floor. The partners, furious with Diane for hurting Lockhart-Gardner’s reputation, discuss how to remove her from the firm. Lockhart Gardner once occupied the twenty-seventh floor; financial difficulties forced them to abandon it early last season. After the firm’s escape from bankruptcy, Will floated the idea of re-renting it. The twenty-seventh floor represents an ideal version of Lockhart Gardner—its once and future glory. But now, the office has been stripped of furniture; throughout the scene, the camera shows the group of partners from a distance, dwarfed by vast emptiness. The distant windows permit only a dim, cold light. The partners’ meeting plays out as a dark parody of the triumphant return Will imagined.

The writers then create a parallel, contrasting scene with Alicia and the rebel fourth years. Like the conclave on the twenty-seventh floor, this meeting is secret, and its attendees are plotting a betrayal of their own. But the mood is cheerful and the setting cozy. The associates cram into Alicia’s living room; a fire in the fireplace provides soft, warm light. Only Alicia—the one character present in both scenes—appears anxious as the others gloat over Lockhart Gardner’s civil war and suggest poaching Diane’s clients. Without drawing any explicit connection, the writers let each of these parallel scenes inform the other. Lockhart Gardner was already an established firm in The Good Wife’s first season, but the fourth years’ camaraderie suggests the youthful enthusiasm of the firm’s beginning. By the same token, having watched the partners scheme against Diane own in their barren former offices, we realize (as Alicia does), that neither youth nor enthusiasm endure, and the shadows of future discord—ambition, distrust, betrayal—already lurk behind the smiling, fire-lit faces.

“A Precious Commodity’s” B Plot proves less effective than its central storyline. Alicia accepts as a pro bono client an undergrad (Tara) serving as a surrogate mother for an infertile couple, Brian and….

After tests reveal an 85% chance the fetus has Patau syndrome, the couple wants the surrogate to abort (as per their contract); she wants to carry the baby to term.

This scenario carries more than enough potential dramatic and political interest. As written, the case proves to be less about abortion than the definition(s) of motherhood, its emotional core located in the confrontations between Kathy and Tara (Brian gets little screen time). The judge’s comment, “I don’t know how to split this decision,” nods to the Judgment of Solomon. Solomon-like, the writers suggest that a “true” mother is the one who puts her child’s interests first—while recognizing the complexity of deciding what those interests consist of, and that a desire to prioritize them derives from cultural pressures and personal belief systems as much as biology.

So why did the case feel unsatisfying?

1) The writers didn’t integrate the case with the Diane/Will narrative. As a result, it felt like a distracting sideshow.

2) 85% is not a sure thing. I can only assume the writers gave the fetus a one in sevenish chance of being born healthy because they wanted to give Tara’s claim at least some validity. However, none of the characters spend much time weighing the odds. Why introduce this plot point if you’re not going to do anything with it?

3) Tara comes across as….kind of dumb. She remarks that she only had a 10% chance of getting into DePaul University, twirls her hair in court, and insists the fact that the fetus is kicking means that it’s healthy. All this would be fine if the writers were trying to present Tara’s viewpoint as without merit—but they’re not.